Practice patterns pertaining to Oncotype DX® testing in specific patient populations: an observational study

Highlight box

Key findings

• Oncotype DX® may not be as efficacious for lobular carcinomas and for patients of varying ethnic backgrounds, specifically African American patients.

What is known and what is new?

• We know the utility of common genomic testing, such as Oncotype DX® and we know that the studies that support it have limited data in certain subsets of patients.

• This manuscript adds data of surgeon preference regarding selection of genomic testing and shows that our ordering patterns may not always be what is most appropriate for patients.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• In the future, ordering patterns and development of novel or updated genomic testing should take certain subsets of patients into account and include a wider variety in research studies to determine the effectivity of a test.

Introduction

Prior to the development of Oncotype DX® in 2004, adjuvant chemotherapy decisions were based upon multidisciplinary discussions regarding clinicopathological features of a patient’s breast cancer, such as: size, nodal status, and grade. In 2018, with the publication of the TAILORx trial examining the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy versus endocrine therapy in patients with midlevel Oncotype DX® scores, Oncotype DX® testing became standard practice and was quickly incorporated into National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. Decisions regarding the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage hormone receptor (HR) positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) negative, axillary nodal negative tumors now focused on a patient’s Oncotype DX® score.

Oncotype DX® testing is a 21 gene expression profiling panel that prognosticates 10-year breast cancer recurrences and survival and predicts the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy. With the update of the TAILORx results in July 2018, it is now utilized for patients with T1–3 HR+ HER2 negative invasive mammary cancers, with up to three positive lymph nodes, who plan to undergo hormone therapy for at least five years (1). Since its groundbreaking development, Oncotype DX® has been widely utilized across the country for both ductal and lobular carcinomas. Further testing in 2021 with the RxPONDER (A Clinical Trial RX for Positive Node, Endocrine Responsive Breast Cancer) evaluated the results of endocrine therapy only versus chemo-endocrine therapy on patients with hormone-receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer, one to three positive axillary lymph nodes (nodal stage N1), and a recurrence score of 25 or lower (2). This trial further showed that postmenopausal women with 21-gene recurrence scores of 0 to 25 with one to three positive axillary nodes have no benefit of chemo-endocrine therapy. Invasive, disease-free survival at 5 years was 91.9% with endocrine therapy alone and 91.3% with chemo-endocrine therapy.

MammaPrint, a similar 70 gene signature test, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2007, and designed to predict distant recurrence risk in early-stage breast cancer. In 2016, the Microarray in Node-Negative and 1 to 3 Positive Lymph Node Disease May Avoid Chemotherapy Trial (MINDACT) evaluated the application of MammaPrint in the selection of patients eligible to not receive chemotherapy (3). MINDACT enrolled 6,693 women with breast cancer [estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-positive, any grade, 0 to 3 nodes positive] and divided them into high and low risk clinically and used MammaPrint to divide them into high and low risk genomically. The trial then focused on the 5-year distant metastasis survival rate of the subset of patients with high clinical risk and low genomic risk who did not receive chemotherapy. The results published in 2016 showed that the select subgroup of high clinical risk, low genomic risk, without chemotherapy had a rate of survival, without distant metastasis, only 1.5% lower than the high clinical risk, low genomic risk group that did receive chemotherapy. The trial’s clinical implications meant that there was a larger subgroup than previously acknowledged who may not require chemotherapy.

As highly personalized genetic testing has gained more traction in the oncology specialties even further genomic tests have been developed including Prosigna, Breast Cancer Index, and EndoPredict. Although we predict that Oncotype DX® is still the most familiar and most widely used, there may be limitations. Oncotype DX® may not be the most accurate to use for lobular carcinomas (4). The lower proliferative activity of lobular cancers may play a role in this testing constraint, as well as other constituents of both the cancer and the test itself. Utility of Oncotype DX® testing may also be limited for African American women, due to inadequate sampling of African American patients in the studies used for test creation and authentication (5). With that being said, genetic markers more prominent in the Black population may not be recognized by the assay. Interestingly, it has also been noted that Black women tend to receive higher Oncotype DX® scores. The cause may lie more in broader race disparities that contribute to diagnosis and evaluation at a later stage in the disease course in comparison to patients of other races.

While Oncotype DX® has served as an immensely useful tool in the examination, prognostic determination, and treatment of breast carcinomas, it is important to highlight its limitations. If specific patient populations are identified as suboptimal for that specific test, we can then hopefully work to tailor new models to better serve those groups of patients.

This study aims to survey breast surgeons throughout the country to further define practice patterns regarding genomic testing. While genomic testing has revolutionized breast cancer treatment, there are limitations to each test that need further explored to guide clinical practice, specifically in regard to how histology, node positivity, and ethnicity may alter testing decisions. We present this article in accordance with the SURGE reporting checklist (available at: https://asj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/asj-24-11/rc).

Methods

An open survey was distributed across the United States to breast surgeons, through the ASBrS Online Forums, as well as the Forums on Mastery of Breast Surgery, to assess practice patterns regarding Oncotype DX® testing versus other genomic testing options for male and female patients with invasive ductal carcinoma (N0, N1) and invasive lobular carcinoma (N0, N1) (see Figure 1). The target sample was breast surgeons, making this a convenience sample in the context of our study. The sample was further limited by those who were members of ASBrS or who frequented the Mastery of Breast Surgery Forums due to the community in which the survey was distributed. The survey was first tested internally with two breast surgeons in our department and deemed easily accessible and feasible for completion and wider distribution. Our survey included the frequency of Oncotype DX® testing in African American patients with the above diagnoses. The survey was created on Google Forms with the promise to participants to uphold anonymity. Participants were only able to complete the survey once—multiple attempts were limited by browser cookies. It included sixteen questions to gather information regarding physician practice setting, experience, familiarity with and preference of genomic testing, especially in the setting of different disease subtypes and nodal disease, as well as for patients of different racial backgrounds. Results auto-populated into a spreadsheet to allow for analysis. Excel equations, formulas, and functions were utilized for analysis, mainly to identify the percentage of survey participants who selected various answers to any given question. A T-Test, also employed through Excel software, was then used to further analyze survey results.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was submitted to the Institutional Review Board of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Central Pennsylvania Region (DHHS OHRP Registration IORG0001079 IRB000001476 FWA00001055). Exemption was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) under 45 CFR 46.104(d)(2). Formal consent was not obtained but study anonymity was ensured and conveyed to participants.

Results

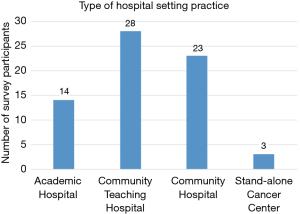

The survey had 90 breast oncology surgeon participants. A little over a third of participants (38.2%) had been in practice for less than 10 years and 50% of participants had been in practice for less than twenty years (see Figure 2). Approximately half (54%) of survey participants come from a suburban setting and work at either a community teaching hospital (31.5%) or community hospital (26%) (see Figure 3). Of the 90 participants surveyed, all were familiar with at least one genomic assay. 98% were familiar with Oncotype, and 88% were familiar with MammaPrint (88%) (see Figure 4). Of note, surgeons were allowed to select as many tests as they were familiar with. The majority of surgeons, 67.8%, were familiar with two (34.4%) to three (33.3%) tests. 10% were familiar with four tests, 10% were familiar with all five tests, and 12.2% were only familiar with one type of test.

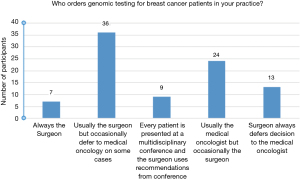

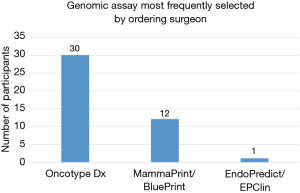

Approximately half of those surveyed (48.5%) stated that in their practice, the surgeon usually ordered the genomic assay testing or would occasionally defer to the medical oncology team for challenging cases (see Figure 5). The surgeons who almost always order their own genomic testing were found to order Oncotype about 70% of the time and MammaPrint about 28% of the time (see Figure 6). The medical oncologist was noted to order genomic testing in 41.6% of participants, with occasional deferment to the surgeon in select cases (see Figure 5).

When asked if a substitute genomic assay was ordered for patients with lymph node positive versus lymph node negative disease, the overwhelming majority (90%) did not choose a different test. For node negative disease, Oncotype DX® was the preferred test in 89% of those surveyed. For the surgeons that did order a different test for lymph node positive disease, MammaPrint was the study of choice (67%).

Histologic subtype did not seem to influence the genomic assay ordered; only 3% of surveyors changed their assay selection when the histologic subtype varied (see Figure 7). Of this group, everyone ordered Oncotype DX® for invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) and everyone ordered MammaPrint for invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC). If there was a mixed histology tumor, these surgeons opted to use Oncotype DX®.

When polled about patient race impacting what genomic test was ordered, 90% of surgeons ordered Oncotype DX® regardless of race and about 10% of surgeons ordered a different test for African American patients (see Figure 8), all choosing MammaPrint as their preferred alternative. Only one physician ordered alternative genomic testing for another non-Caucasian race, and it was for those of Southeast Asian ethnicity.

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed in women, with invasive lobular carcinoma second to invasive ductal carcinoma as the top two most diagnosed subtypes (6,7). Approximately 10–15% of diagnosed breast cancer cases each year are invasive lobular carcinoma (7). Genetic profiling has solidified a prominent role in the post-cancer diagnosis discussion. Multigene assays, such as Oncotype DX®, evaluate tumor biology to assess pathologic risk and need for chemotherapeutic treatment. They are beneficial to the health system as a whole in terms of cost reduction as a result of less overtreatment. One study even identified reduction in green-house gas emission as a downstream result due to less travel for outpatient visits (8). Oncotype DX® is used worldwide. It was first introduced into practice shortly after its development in 2004. It utilizes reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction to evaluate mRNA and evaluate distinct biological activities inherent to the tumor. Its use was initially described for ER-positive, node-negative early stage breast cancers. Other genomic assays include EndoPredict® (EP), Breast Cancer Index (BCI), Predictor Analysis of Microarray 50 (PAM50), and MammaPrint®. It is recommended that for any given patient, only one assay should be used to avoid discordance (1). Briefly, EP is an 11-gene RNA assay that classifies tumor risk. BCI evaluates two biomarkers to compute a prognostic score, recurrence risk, and assist in determining duration of endocrine therapy beyond the normally recommended timeline. PAM50 is a 50-gene test using mRNA and can be used for patients with up to three positive nodes in the setting of ER-positive early stage breast cancer. MammaPrint, also known as the Amsterdarm 70-gene profile, also classifies tumor risk. Something that makes Oncotype DX® stand out is its ability to predict chemotherapeutic benefit, whereas the other assays mainly highly prognosis and risk and their utility as a tool to guide treatment is not validated (1).

As mentioned previously, different variables are important to identify to best approach genomic assay evaluation and its specific limitations. Invasive lobular carcinomas, while known for having an abundance of estrogen receptors, have not been the primary histologic subset of breast cancer used in studies to validate Oncotype DX®’s results (9). This study investigated practice patterns of established breast cancer surgeons in utilizing genomic profiling. Most surgeons polled had less than 10 years of attending experience (38.2%) which lends the idea that these surgeons are up to date with recent studies regarding genomic profiling, as its use has surged in recent years. Additionally, most of these surgeons were based out of a community/teaching hospital (31%), which requires continuously reading and learning the most up-to-date practices in order to teach residents. Seventy percent of polled attendings order Oncotype DX® most frequently. As that is the test utilized the longest, this was no surprise. In this study, we were particularly interested in genomic assay ordering habits in the setting of invasive ductal carcinoma versus invasive lobular carcinoma. 96% of our respondents did not change their genomic test preference based on histologic subtype and 90% ordered Oncotype DX® regardless of race. Recent studies have shown that both of those subtypes of patients may decrease the accuracy of the score generated by Oncotype DX® (5).

Prior research has suggested that there may be differences in the effectivity of Oncotype DX® in ethnic minorities, specifically the African American population (5,10). A study by Robinson et al., published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology in 2021, compared concordance of two genomic assays (Oncotype DX®vs. MammaPrint) in an African American cohort. Results revealed a 51% discordance between Oncotype DX® score and MammaPrint score in African American females (11). Discordance was most notable in low risk cases scored on Oncotype DX® testing [recurrence score (RS) ≤25]; about 60% of tumors with TAILORx intermediate RS (between 11–25) were considered to have high risk scoring on MammaPrint. This study also revealed that African American patients with a low or intermediate RS have higher recurrence rates and lower overall survival compared to Caucasian patients with early breast cancer, with the same RS (11).

According to the American Cancer Society, African American women have a 41% higher mortality rate from breast cancer compared to their Caucasian counterparts, despite similar or lower incidence rates. The wide breast cancer disparity reflects both later stage at time of diagnosis and lower 5-year survival overall (12).

Furthermore, a recent study published in JAMA Oncology in 2021 studied 86,033 patients and found that African American women were more likely to have a higher recurrence score than their white counterparts (5). Many factors may be involved in this finding. For example, the original genomic profiling models were not based off diverse populations; this raises the question if these tests need to be re-calibrated. With this new awareness of disparity, is proper information being disseminated to or addressed by physicians to order the best score for their individual patient? Personalized medicine has been a concept gaining momentum over the past decade and histology, node positivity, and ethnicity need to be recognized in clinical decision making.

Conclusions

Oncotype DX® has been a widely used genomic assay since its creation in 2004. Due to its longevity, it has been validated by numerous research trials and is typically the genomic screening assay of choice for ER+ breast cancers. With genomic testing transforming clinical practice further research and education may be needed to determine best testing practice in regard to histology, node positivity, and ethnicity and their role in interpreting genomic testing outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SURGE reporting checklist. Available at: https://asj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/asj-24-11/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://asj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/asj-24-11/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://asj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/asj-24-11/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was submitted to the Institutional Review Board of University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Central Pennsylvania Region (DHHS OHRP Registration IORG0001079 IRB000001476 FWA00001055) and approved for exemption under 45 CFR 46.104(d)(2). Formal consent was not obtained but study anonymity was ensured and conveyed to participants.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Siow ZR, De Boer RH, Lindeman GJ, et al. Spotlight on the utility of the Oncotype DX(®) breast cancer assay. Int J Womens Health 2018;10:89-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalinsky K, Barlow WE, Gralow JR, et al. 21-Gene Assay to Inform Chemotherapy Benefit in Node-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2336-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cardoso F, van't Veer LJ, Bogaerts J, et al. 70-Gene Signature as an Aid to Treatment Decisions in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:717-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Göker M, Denys H, van de Vijver K, et al. Genomic assays for lobular breast carcinoma. J Clin Transl Res 2022;8:523-31. [PubMed]

- Hoskins KF, Danciu OC, Ko NY, et al. Association of Race/Ethnicity and the 21-Gene Recurrence Score With Breast Cancer-Specific Mortality Among US Women. JAMA Oncol 2021;7:370-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:7-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mouabbi JA, Hassan A, Lim B, et al. Invasive lobular carcinoma: an understudied emergent subtype of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2022;193:253-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vanni G, Materazzo M, Portarena I, et al. Socioeconomic Impact of OncotypeDX on Breast Cancer Treatment: Preliminary Results. In Vivo 2023;37:2510-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsai ML, Lillemoe TJ, Finkelstein MJ, et al. Utility of Oncotype DX Risk Assessment in Patients With Invasive Lobular Carcinoma. Clin Breast Cancer 2016;16:45-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ibraheem A, Olopade OI, Huo D. Propensity score analysis of the prognostic value of genomic assays for breast cancer in diverse populations using the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer 2020;126:4013-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson PA, Tsai ML, Lo SS, et al. Genomic risk classification by the 70-gene signature and 21-gene assay in African American early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:e12568. [Crossref]

- Giaquinto AN, Miller KD, Tossas KY, et al. Cancer statistics for African American/Black People 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72:202-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Cox D, Stein H, Shpigel M, Barton K, Aboushi R. Practice patterns pertaining to Oncotype DX® testing in specific patient populations: an observational study. AME Surg J 2024;4:7.