Malignant phyllodes tumor with axillary metastases: a case report

Highlight box

Key findings

• We present a case of malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast with axillary lymph node metastasis; with unclear tumor type at the time of presentation treated with mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy, and completion axillary lymph node clearance. This was followed by postoperative chemotherapy and the option for postoperative radiation.

What is known and what is new?

• There is no recommendation for surgical axillary staging in phyllodes tumors, but this case poses a question of whether there is a role for performing axillary surgery during excision if suspicion for metastatic disease is high enough. It also poses questions about the occasional use of adjuvant chemotherapy, and radiation.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Robust guidelines for postoperative management in this patient population are lacking and more data is necessary to shed light on optimal management.

Introduction

Phyllodes tumors are rare fibroepithelial tumors that represent less than 1% of all breast tumors (1). Based on the newest edition of World Health Organization (WHO) classifications for breast pathology, phyllodes tumors are further classified into benign, borderline and malignant phyllodes tumors. Loss of epithelial interaction in the stroma is believed to lead to malignant progression. In benign phyllodes tumors, stromal atypia is mild, stromal cellularity is only mildly increased, stromal overgrowth is absent, and mitotic count <5/10 high powered field (HPF) or <2.5/mm2, the tumor border is well defined and there are no malignant heterogenous elements. Conversely malignant phyllodes have marked stromal atypia, stromal cellularity is markedly and diffusely increased, stromal overgrowth is present, and mitotic count is ≥10/10 HPF or ≥5/mm2, tumor borders are diffusely permeative and there are malignant heterogenous elements present (2).

Recent literature reports that 10–15% of phyllodes tumors are malignant and approximately 9–27% of patients with malignant phyllodes tumor have metastasis to distant organs. Metastatic involvement of axillary lymph nodes was only seen in 2% of cases (3).

While the surgical management of phyllodes tumors has been addressed many times in the literature, there have been few reports involving axillary metastases. We present a case report of a patient with a malignant phyllodes tumor with axillary metastasis to further understand optimal treatment for this patient population. We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://asj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/asj-23-54/rc).

Case presentation

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Verbal informed consent for publication of this case report and accompanying images was obtained from the patient.

A 34-year-old premenopausal woman with a past medical history significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and morbid obesity presented with a self-palpated right breast mass. The patient first noticed the mass several years prior to her presentation, but the mass had rapidly grown in size over the months prior to presentation. Physical exam of the right breast on first encounter was notable for an appropriately 12 cm grapefruit sized mass with a somewhat cystic nodular appearance in areas involving the breast skin, centered at 4:00. This was also involving the nipple with some serosanguinous discharge from the area of skin when the biopsy site was. There was no right-sided axillary lymphadenopathy apparent by exam but exam was limited by body habitus. Physical exam of the left breast/axilla was benign. In the time between initial exam/procedures and surgery the overlying skin further ulcerated to expose the underlying tumor (Figure 1).

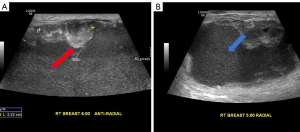

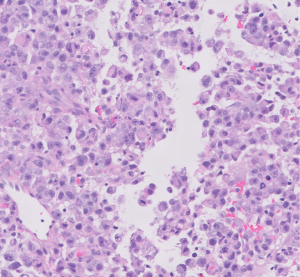

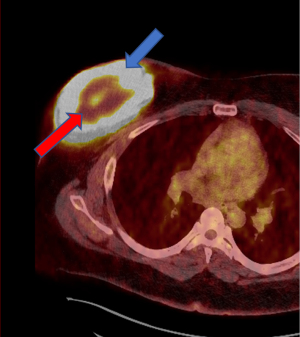

Evaluation at an outside institution with bilateral breast tomograms and right breast sonogram revealed an 11.2 cm round mass with central necrosis and a thick wall with mural nodularity (Figures 2,3). An ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the right breast was consistent for a high-grade malignant neoplasm of indeterminant origin (Figure 4). Staging imaging confirmed 1 abnormal lymph node in the inferomedial right axilla, measuring 1.4 cm with replacement of fatty hilum. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a necrotic appearing mass in the breast contiguous with skin, and a morphologically abnormal level I axillary node. Subsequent ultrasound biopsy of lymph node was done and was benign, and felt to be concordant by performing radiologist. No other systemic metastases were identified (Figure 5). A comprehensive multigene panel blood test for hereditary cancer was negative for inherited genetic mutations. Preoperative computed tomography (CT) chest with positron emission tomography (PET)-CT of skull base to mid-thigh demonstrated intense fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in the breast, no pectoralis muscle invasion and sub-centimeter ipsilateral axillary nodes with minimal non-specific FDG activity.

The patient met with a breast surgeon and medical oncologist and had a radiologic and pathologic review of her case. There was consensus that surgery would be the best first step given the unclear diagnosis of the tumor type. She underwent a right mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Intra-operative frozen pathology of the sentinel lymph node biopsy confirmed metastatic disease and the patient went on to have a completion axillary lymph node clearance. A plastic surgeon performed skin mobilization and closure over the wide excision. She did not have breast reconstruction.

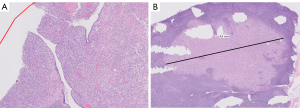

Gross examination of the mastectomy specimen demonstrated a hemorrhagic and friable mass measuring 14.0 cm × 13.0 cm, located in the central breast and extending into the dermis with skin ulceration. Approximately 70–80% of the tumor was necrotic. Extensive sampling to include the entire viable tumor and select areas of necrosis were submitted for evaluation. On histologic examination, the tumor showed a predominant stromal component of spindled to ovoid cells with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli, similar to the biopsy specimen. There were also markedly atypical globoid cells with dense eosinophilic cytoplasm suggestive of rhabdomyoblasts. However, CDK4, MDM2, desmin and myoD1 were negative. The morphology and immunophenotype of the stromal component is best classified as a pleomorphic sarcoma with rhabdoid features. Comprehensive sampling of the tumor also revealed focal leaf-like architecture with periductal stromal condensation. The tumor showed brisk mitotic activity ranging from 4–17 per high power field. No lymphovascular invasion was seen. A broad panel of immunohistochemical stains were performed. The tumor was positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and negative for epithelial markers, AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, 34Be12, CK7 and breast specific marker GATA3. The tumor showed retained nuclear expression for SMARCA4 (BRG-1) and SMARCB1 (INI-1). Final pathology revealed a malignant phyllodes tumor with pleomorphic sarcoma, measuring 14 cm × 13 cm, 0.7 cm from the anterior margin and 1.2 cm from the posterior margin on the primary specimen. Addition skin take was benign. Two out of 17 lymph nodes were positive for disease with the largest focus 0.45 cm in size. No additional tumor foci were found (Figure 6).

The case was presented at multidisciplinary tumor board. Available data on adjuvant therapy for malignant phyllodes tumors was reviewed. There was limited data due to the rarity of this histologic diagnosis, and no definitive data to demonstrate clear benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy for malignant phyllodes tumors. However, given the size of the patient’s tumor (>10 cm), lymph node involvement (rare to have phyllodes involving axillary nodes), high mitotic activity (>10/HPF) and extensive necrosis, it was determined that there was an increased risk of recurrence and the consensus from the breast oncology tumor board and sarcoma oncology team, was to offer adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy given the high-risk nature of the tumor.

The patient received adjuvant doxorubicin/ifosfamide for 2 cycles. The ifosfamide was discontinued due to hemorrhagic cystitis and generalized pruritic hives during infusions. The patient was then transitioned to doxorubicin/dacarbazine for the remaining 4 cycles, with a total of 6 cycles. The patient initially had planned to undergo adjuvant radiotherapy, and met with radiation oncology, but did not follow through due to psychosocial challenges and right arm stiffness limiting range of motion. She underwent physical therapy. There was no evidence of recurrence at 1 year follow-up imaging and exam. The patient was most recently seen without clinical evidence of recurrent disease at 2.5 years of follow-up. Repeat systemic imaging is currently pending (Table 1).

Table 1

| Timepoint | Event |

|---|---|

| 2014 | Patient first notices breast mass, ultrasound at outside hospital with benign findings |

| 2022 | Presented as new patient to our hospital system, with workup imaging and biopsy revealing a locally advanced ulcerating breast tumor of unclear type |

| 2 months later | Underwent right mastectomy and axillary node clearance |

| 2 months later | Started chemotherapy |

| 2 months later | Switched chemotherapy regimens due to side effects |

| 2 months later | Chemotherapy finished |

| 1-year follow-up | No evidence of recurrent disease on imaging and exam |

| 2.5-year follow-up | No evidence of recurrent disease on exam, imaging pending |

Discussion

Phyllodes tumors are fibroepithelial neoplasms characterized histologically by epithelial and cellular stromal components (1). They can often mimic fibroadenomas and often do not often demonstrate specific imaging features that allow a clear differentiation between benign masses and tumors. This is the case with pathology as well, tumors are often not identified on core biopsy. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to include phyllodes tumors in their differential diagnosis of a breast mass, especially a rapidly growing breast mass.

Phyllodes tumors can range from benign, to borderline, to malignant. Malignant phyllodes tumors have the propensity to metastasize, but typically their pattern of metastasis is hematogenous rather than lymphatic. Thus, axillary metastasis is very rare and routine axillary staging is not recommended for phyllodes tumors, but should be considered if lymph nodes are pathologic on clinical exam, and occur more frequently if tumor is necrotic (4). However, in this case, axillary staging was performed as the tumor type was undetermined, additionally the tumor was necrotic, and the axilla was suspicious pre-operatively. This poses a reminder that axillary staging should be considered for phyllodes tumors with significant necrosis at presentation and when clinical suspicion for axillary metastasis is present.

To date, there are no randomized trials in the treatment of malignant phyllodes tumors. The current National Cancer Comprehensive Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend wide local excision with the goal of achieving ideally 1 cm or wider margins without axillary staging unless clinically concerning (5). Mastectomy has not shown a survival advantage over wide local excision (6). Lymph node involvement is rare and has been reported in the literature with incidences ranging from 1.1–3.8% (7).

In this report, we present a case of locally advanced necrotic breast tumor of undetermined etiology with a suspicious lymph node by ultrasound examination but biopsied benign, so mastectomy and sentinel lymph node biopsy were performed first line. Sentinel node was positive on frozen section, and a completion axillary lymph node clearance was thus performed.

There is no large trial data to guide management of malignant phyllodes tumors and the involvement of axillary lymph nodes is exceedingly rare, and thus the evidence-based adjuvant management of this particular patient is even more challenging. The use of adjuvant therapy is controversial for malignant phyllodes tumors. The utility of chemotherapy is variable but considered given the high risk of recurrence and metastasis and is typically guided by soft tissue sarcoma guidelines rather than breast cancer guidelines. Doxorubicin with dacarbazine compared to no medical therapy has been studied with no benefit in relapse free survival (8). However, since phyllodes tumors are considered soft-tissue sarcomas, adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin plus dacarbazine may provide some benefits to patients with large (>5.0 cm), high-risk tumors as is the case for our patient (8). Recently, doxorubicin and ifosfamide therapy have been reported to be effective to treat metastases of malignant phyllodes tumors, which was the initial chemotherapy regimen for our patient (9,10).

Because of the risk of local recurrence of malignant phyllodes tumors, the question about the role for adjuvant radiation is often discussed. Recommendation for or against radiation is not definitive per NCCN guidelines (5). With regards to adjuvant radiation, several studies have shown that radiation with breast conservation and mastectomy has not demonstrated improved cancer specific survival (11). Conversely, other studies have reported that radiotherapy was associated with superior local control rate at long term follow-up for both borderline and malignant phyllodes tumors (12). Given the aggressive and advanced nature of our patient’s malignant phyllodes tumor with axillary metastases, she was advised after multidisciplinary discussion, to have adjunctive radiotherapy, but ultimately did not carry out this suggested treatment.

To help guide management of malignant phyllodes patients, it is important to determine predictors of malignant behavior. Tumor size, cytological atypia, mitotic rate and stromal overgrowth are examples of such predictors. Some of the factors which have shown an increased local recurrence include tumor size, positive surgical margins, stromal overgrowth, high mitotic count, and necrosis (12). Early diagnosis and staging of phyllodes tumors are vital to guiding management and improving overall outcome of the disease after treatment. Therefore, if even a benign, biopsied breast mass is continually growing, it should be flagged for further workup. Lastly, given the limited data on this relatively rare cancer, case reporting is important. For management decisions for these patients, multidisciplinary input is critical.

Conclusions

Few cases of malignant phyllodes with lymph node metastasis have been reported. We present a case of malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast with axillary lymph node metastasis at the time of presentation treated with mastectomy and axillary lymph node clearance followed by adjuvant therapy. There is a very selective role for axillary surgery in phyllodes tumors, specifically for necrotic malignant phyllodes tumors with suspicious clinical axillae. This case poses an example where axillary surgery should be incorporated. Soft tissue sarcoma guidelines, and multidisciplinary input should ultimately guide decisions about any role for adjuvant systemic therapy as most phyllodes patients do not need chemotherapy. The role for radiation therapy should also be determined on a multidisciplinary basis. Robust data for postoperative management in this patient population is lacking, and accrual of more data is necessary to shed light on optimal management.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://asj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/asj-23-54/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://asj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/asj-23-54/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://asj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/asj-23-54/coif). J.L. is an unpaid member of the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBRS) membership committee. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Verbal informed consent for publication of this case report and accompanying images was obtained from the patient.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Parker SJ, Harries SA. Phyllodes tumours. Postgrad Med J 2001;77:428-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan PH, Ellis I, Allison K, et al. The 2019 World Health Organization classification of tumours of the breast. Histopathology 2020;77:181-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Treves N. A study of cystosarcoma phyllodes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1964;114:922-36. [Crossref]

- Mangi AA, Smith BL, Gadd MA, et al. Surgical management of phyllodes tumors. Arch Surg 1999;134:487-92; discussion 492-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical breast guidelines in oncology. Breast cancer. Accessed November 11, 2024. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf

- Reinfuss M, Mituś J, Smolak K, et al. Malignant phyllodes tumours of the breast. A clinical and pathological analysis of 55 cases. Eur J Cancer 1993;29A:1252-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shafi AA, AlHarthi B, Riaz MM, et al. Gaint phyllodes tumour with axillary & interpectoral lymph node metastasis; A rare presentation. Int J Surg Case Rep 2020;66:350-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morales-Vásquez F, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Broglio K, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin and dacarbazine has no effect in recurrence-free survival of malignant phyllodes tumors of the breast. Breast J 2007;13:551-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto S, Yamagishi S, Kohno T, et al. Effective Treatment of a Malignant Breast Phyllodes Tumor with Doxorubicin-Ifosfamide Therapy. Case Rep Oncol Med 2019;2019:2759650. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turalba CI, el-Mahdi AM, Ladaga L. Fatal metastatic cystosarcoma phyllodes in an adolescent female: case report and review of treatment approaches. J Surg Oncol 1986;33:176-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim YJ, Kim K. Radiation therapy for malignant phyllodes tumor of the breast: An analysis of SEER data. Breast 2017;32:26-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roberts N, Runk DM. Aggressive malignant phyllodes tumor. Int J Surg Case Rep 2015;8C:161-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Lifrieri A, Zeng J, Mohabbatizadeh B, Lehman J. Malignant phyllodes tumor with axillary metastases: a case report. AME Surg J 2024;4:24.