Adult thoracolumbar deformity: critical appraisal of radiographs, understanding the angles, and predictors of optimal patient improvement—a review

Introduction

Background

Thoracolumbar adult spinal deformity (TL-ASD) is a highly heterogeneous disorder that often results in considerable functional and psychological disability in adults. Surgical intervention and correction of TL-ASD has consistently been demonstrated to provide superior improvement in health-related quality of life compared to nonoperative management (1-8). While a variety of factors dictate short- and long-term outcomes of operations for TL-ASD, one of the most critical, dynamic, and elusive aspects is restoration of appropriate and “optimal” radiographic spinal alignment in both the coronal and sagittal planes (9). In fact, Passias et al. reported that patients with optimal spinal radiographic alignment post-operatively had fewer late complications (mechanical and reoperations), which resulted in better cost-utility at 1 year and maintained lower overall cost and costs per quality adjusted life years at 2 years compared to non-optimally aligned patients (9).

Rationale and knowledge gap

While prior reviews have been conducted on radiographic alignment in adult spinal deformity (ASD), few have provided a comprehensive review of both coronal and sagittal spinal alignment parameters and how they each influence patient outcomes following surgical correction of ASD. Additionally, none have incorporated the most up-to-date concepts of pelvic angles (i.e., L1 and T4) with respect to post-operative outcomes.

Objective

As achieving optimal surgical correction is critical for long-term success, we present a comprehensive review of the most up-to-date radiographic spinal alignment parameters with a critical focus and appraisal of their relative associations with patient outcomes.

Coronal spinal alignment

The “Spinal Deformity Study Group (SDSG) Radiographic Measurement Manual” provides a comprehensive review of key coronal alignment radiographic parameters (10).

Regional coronal radiographic alignment parameters

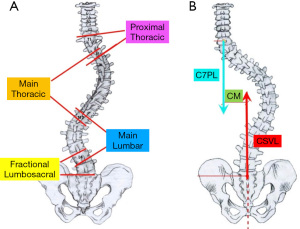

Degenerative pathology, but also neuromuscular, congenital, traumatic, and/or pathological processes can result in coronal spinal deformities in adults. The Cobb angle, which is measured from the superior end plate of the most cephalad end vertebra to the inferior end plate of the most caudal end vertebra within the curve, is used to assess the magnitude of each scoliotic curve (Figure 1) (10). The “major curve” is used for the curve with the greatest magnitude, while the term “compensatory curve(s)” is used to describe the less severe curves. In adults, a major lumbar/thoracolumbar curve and a compensatory lumbosacral fractional curve from L3 or L4 to S1 are the most common curves (Figure 1) (11).

Global coronal radiographic alignment parameters

Overall global coronal alignment and magnitude of truncal deviation is determined by the distance between the following two vertical lines (Figure 1).

- C7 plumb line (C7PL): vertical line drawn perpendicular to the floor or drawn parallel to the radiograph edge from the C7 centroid.

- Central sacral vertical line (CSVL): vertical line drawn perpendicular to the floor from the geometric center of S1 that depicts the coronal position of the spine in relation to the pelvis (drawn parallel to the radiograph edge) (Figure 1) (11).

Association of coronal radiographic alignment parameters with patient outcomes

While the current prevailing sentiment is that adult coronal malalignment jeopardizes patient reported outcomes (PROs), albeit this understanding is incomplete and continues to evolve (12-16). Pre-operative global coronal malalignment >4 cm was reported by Glassman et al. in 2005 to portend significantly greater pain and disability [Short-Form 12 Health Survey (SF-12), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Scoliosis Research Society-22 Questionnaire (Revised) (SRS-22r)] compared to <4 cm of coronal malalignment (12). The International Spine Study Group (ISSG) more recently concluded that a shift in CSVL <3 cm should be considered a potential coronal realignment target threshold given residual post-operative global coronal malalignment of >3 cm was associated with worse SRS-22r Appearance and Satisfaction scores (13). The threshold of associated disability has been further refined to <2 cm, as Boissiere et al. found that starting at a 2 cm offset, global coronal malalignment independently affects PROs with disability increasing linearly with greater CSVL deviation (14). Furthermore, Baroncini et al. reported that patients with a residual coronal malalignment <2 cm have 3.5 times greater odds of achieving the SRS-22 scores’ minimally clinically important difference (15).

The relative importance of shoulder asymmetry, a residual rib hump, a residual lumbar prominence, torso translation, and regional Cobb magnitudes compared to global coronal alignment in TL-ASD is not known. Whether global coronal imbalance with symmetric shoulder heights is preferred cosmetically and functionally to “normal” global coronal alignment with asymmetric shoulders is not known and deserves further investigation.

Sagittal spinal alignment

Compared to the coronal plane, radiographic parameters to assess the sagittal plane’s profile are more numerous.

Regional sagittal radiographic parameters (Figure 2)

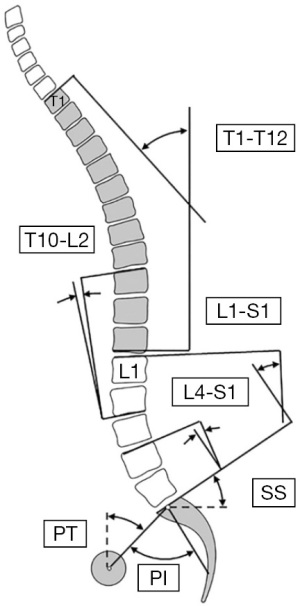

A fundamental understanding of the sagittal plane starts with assessment of the following lumbopelvic radiographic parameters and regional sagittal alignment parameters:

- Pelvic incidence (PI): angle between a line perpendicular to the mid-point of the sacral endplate and a line through the midpoint of the sacral endplate to the axis of the femoral heads.

- Pelvic tilt (PT): angle between a vertical line and a line through the mid- point of the sacral endplate to the axis of femoral heads.

- Sacral slope (SS): angle made between a horizontal line and S1’s endplate.

- L4–S1 lordosis: sagittal Cobb angle between the superior endplate of L4 and the superior endplate of S1.

- L1–S1 lordosis: sagittal Cobb angle between the superior endplate of L1 and the superior endplate of S1.

- Thoracic kyphosis: while commonly defined as the sagittal Cobb angle between T5’s superior and T12’s inferior endplate, it has also been described to be measured from the superior endplate of T2 to the inferior endplate of T12 and from the superior endplate of T4 to the inferior endplate of T12.

- Thoracolumbar kyphosis (T10–L2): sagittal Cobb angle between the superior endplate of T10 and the inferior endplate of L2.

Global sagittal radiographic parameters (Figure 3)

Assessment of global sagittal alignment is assessed with the following radiographic parameters, which take into consideration the position of the head and entire spine relative to the pelvis and lower extremities as well as the positions of the thoracic and lumbar spines relative to the pelvis.

- Cranial sagittal vertical axes (CrSVA): the horizontal distances between the cranium’s center of mass’ (nasion-inion midpoint) vertical plumb line to the sacrum (CrSVA-S), hip (CrSVA-H), knee (CrSVA-K), and ankle (CrSVA-A) (17-19).

- C2–S1 sagittal vertical axis (C2–S1 SVA): distance from the posterior-superior corner of S1’s endplate to the C2 plumb line.

- C7–S1 SVA: distance from the posterior-superior corner of S1’s endplate to the C7PL.

- Vertebral-pelvic angles:

- C2 pelvic angle (C2PA): angle subtended by a line from the femoral heads to the center of the C2 vertebral body and a line from the femoral heads to the center of the superior sacral end plate.

- T1 pelvic angle (T1PA): angle subtended by a line from the femoral heads to the center of the T1 vertebral body and a line from the femoral heads to the center of the superior sacral end plate (20).

- T4 pelvic angle (T4PA): angle subtended by a line from the femoral heads to the center of the T4 vertebral body and a line from the femoral heads to the center of the superior sacral end plate (21,22).

- L1 pelvic angle (L1PA): angle subtended by a line from the femoral heads to the center of the L1 vertebral body and a line from the femoral heads to the center of the superior sacral end plate (21-23).

Association of sagittal radiographic alignment parameters with patient outcomes

An appreciation for the association between sagittal alignment radiographic parameters and functional outcomes was first noted in 2005. In his seminal article, Glassman et al. reported a significant correlation between increasing global sagittal imbalance, as measured by the C7–S1 SVA, and patient-reported outcomes (lower general function scores, as assessed by SF-12 scores, as well as greater disability, as assessed by the ODI) (12). This was followed by reports from Terran et al. and Smith et al. that demonstrated that global as well as regional radiographic sagittal alignment parameters, specifically PT and PI-lumbar lordosis (PI-LL) mismatch, were also associated with health-related outcome scores (24,25). As a result, the “Schwab Modifiers” for the sagittal plane were introduced and provided an initial framework for sagittal alignment targets that included PI-LL <10°, PT <20°, and C7-S1 SVA <4 cm (24). These thresholds were subsequently modified by the ISSG to incorporate age given that appropriate sagittal alignment was determined to vary across different age ranges (26). Specifically, Lafage et al. noted that ideal spinopelvic parameter values increased with age, ranging from PT of 10.9°, PI-LL of −10.5°, and SVA of 4.1 mm for patients younger than 35 years old to PT of 28.5°, PI-LL of 16.7°, and SVA of 78.1 mm for patients older than 75 years of age (26). As such, it was concluded that, “operative realignment targets should account for age, with younger patients requiring more rigorous alignment objectives” (26).

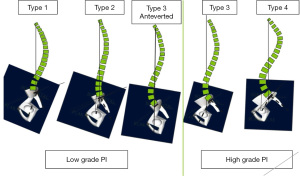

While these thresholds provided an important preliminary understanding of surgical sagittal alignment goals, they should be considered relatively simplistic and not comprehensive given they do not account for the influence of pelvic morphology on sagittal alignment. In 2002, Vaz et al. performed a prospective analysis of 100 healthy young adults so as to create a database of positional parameters of the pelvis and the spine in asymptomatic patients (27). They reported that there were considerable variations in PI (average 51.7°±11.5°, range, 33° to 85°), PT (average 12.3°±5.9°, range, –1° to 27.9°), and L1–S1 lordosis (average 46.5°±11.1°, range, 26° to 76°) with each following a bell-curve distribution and that PI magnitude was significantly correlated to LL and PT (27). This was followed in 2005 by Roussouly et al. describing the normal variation of sagittal alignment among 160 healthy adult volunteers based on LL, PI, and the inflection point from LL to thoracic kyphosis to attempt to stratify the shapes of an asymptomatic spine into four curve types differentiated by low or high SS and characterization of lumbar lordotic curve (28) (Figure 4). This was updated in 2018 to include a 5th part to the classification that included an anteverted pelvis (29) (Figure 4). Despite being relatively qualitative in nature, numerous studies have found that restoring the sagittal shape recommended by Roussouly decreases mechanical complications post-operatively (30-33).

The connection between LL shape and PI was further refined by Pesenti et al. who found that overall shape of the lumbar spine is directly correlated to PI magnitude (34). More specifically, Pesenti et al. reported that lordosis in the proximal aspect of the lumbar spine (L1–L4) varied based on PI magnitude with patients with low PIs having 33% of their total lordosis coming from the L1–4 segments and high PI patients having nearly 50% of their total lordosis coming from the L1–4 segments (34). Alternatively, lordosis from the distal lumbar spine (L4–S1) remained relatively constant at 35–40° irrespective of PI magnitude (34).

With these aforementioned concepts in mind, the European Spine Study Group (ESSG) devised the Global Alignment and Proportion (GAP) score, which is a quantitative, PI-based proportional scoring system to analyze spinopelvic alignment with the goal to predict mechanical complications after TL-ASD (35). The GAP score is devised from the following five categories (35):

- Age (<60 vs. >60 years);

- Lordosis Distribution Index (LDI) = [(L4–S1 lordosis)/(L1–S1 lordosis)] * 100%;

- Relative LL (RLL) = (measured LL) − (ideal lordosis = (PI * 0.62 + 29));

- Relative pelvic version (RPV) = (measured SS) −(ideal SS = (PI * 0.59 + 9));

- Relative spinopelvic alignment (RSA) = (measured global tilt) − (ideal global tilt = (PI * 0.48 − 15)).

While the original validation’s results demonstrating the GAP score to be predictive of mechanical complications after TL-ASD have been corroborated by several additional investigators (36-38), acceptance of the GAP score as is not universal given contradicting reports (39-43).

Defining and understanding the ideal sagittal alignment based on global spinal shape and its relative regional positions relative to the pelvis and lower extremities have been areas of active investigation. To this end, the aforementioned vertebral pelvic angles (VPA: T1PA, T4PA, L1PA) and CrSVA measurements provide complementary information to the regional radiographic alignment goals, the Roussouly classification, and the GAP score. The T1PA was introduced in 2014 by Protopsaltis et al. as a unique measure of sagittal alignment that simultaneously accounts for pelvic retroversion and spinal inclination (20). In this original investigation it was found that T1PA correlated with C7–S1 SVA, PI-LL, and PT and that increasing T1PA (<10°, 10–20°, 21–30°, >30°) revealed a significant and progressive worsening in health-related quality of life with a T1PA of 20° corresponding to an ODI >40 (severe disability) (20). Based on these data, a target T1PA of <14° was recommended (20). Other investigators have also found T1PA to be predictive of patient outcomes (ODI, SRS-22) after TL-ASD, albeit their recommended targets varied (<10–20°) (44,45).

Most recently, the T4PA and L1PA have garnered more attention given their strong associations with patient outcomes following TL-ASD. In normative international cohorts, Hills et al. demonstrated that the L1PA accounts for magnitude and distribution of lordosis and is strongly associated with PI and T4PA (within 4° of L1PA) (21). Subsequently, in a prospective multicenter study of 247 TL-ASD patients, Hills et al. found that deviation, in either direction, from a normal L1PA (PI × 0.5 − 21°) or T4–L1PA mismatch was associated with a significantly higher risk of mechanical failures, independent of age (22). Additionally, risk was minimized with an L1PA of PI × 0.5 − (19°±2°) and T4–L1PA mismatch between −3° and +1° (22). While Chanbour et al. also found that achieving ideal L1PA ± 5° was associated with a significant decreased risk of rod fracture/pseudarthrosis, there was no association between achieving ideal L1PA and patient-reported outcomes (23).

In addition to intraspinal global alignment parameters, radiographic measures that account for total body sagittal alignment and include the cranium and lower extremities have gained recent notoriety. The four CrSVA measures, as defined above, have been demonstrated to have stronger associations with preoperative patient-reported outcome measures (ODI, SRS-22) than C7–S1 SVA (17,18). Specifically, in multivariable linear regression models, CrSVA-H and CrSVA-A were found to be the strongest sagittal alignment variables for pre-operative health-related of life outcome measures (17,18). And, most recently in 2024, Lai et al. found that CrSVA-H alignment surpassed C7–S1 SVA as a significant, independent predictor of 2-year SRS-22r scores, which led to the conclusion that it (CrSVA-H), “should be considered as one of the standard postoperative sagittal alignment target goals” (19).

Relative utility and importance of sagittal alignment parameters

That there exist so many different methods to assess sagittal spinal alignment raises the inherent question of which approach is most accurate and most predictive of patient outcomes. The literature provides some answers to this inquiry, albeit incomplete and conflicting. In 2019, Jacobs et al. found that while both Schwab classification/modifiers and the GAP score were capable of predicting mechanical complications, the GAP score proved to be significantly more appropriate given that all parameters are related to individual PI (46). Subsequently, in 2021 Passias et al. evaluated 103 operative TL-ASD patients and concluded both matched Roussouly type and improved Schwab modifiers had superior PROs at 2 years (47). Thus, concurrent consideration of both systems may offer utility in establishing optimal realignment (47). Most recently in 2024, Pizones et al. reported that the T4–L1-hip axis and the GAP score showed potential in predicting adverse events, surpassing the Roussouly method, in a cohort of 391 TL-ASD operative patients (48). Lastly, Das et al. reported that while respecting VPA individually may help prevent development of proximal junctional pathology, the value of VPA can be augmented when integrated with the GAP score and sagittal age-adjusted scores to prevent complications and improve quality of life (49). In sum, these overlapping results suggest that adhering to PI-based alignment strategies (i.e., GAP score, T4–L1-hip axis) and recreating appropriate spinal shape based on Roussouly classification all likely play a role in the short- and long-term outcomes of patients. However, these data also need to take into consideration the increasing evidence that radiographic correction does not always correlate with clinical outcomes, as patient outcomes are complex and likely influenced by many patient and surgical factors (50-53).

Summary of proposed radiographic sagittal alignment targets

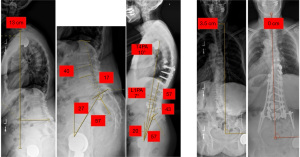

Given the collective literature discussed above, we present in Table 1 a PI-based framework by which one may use to plan pre-operatively and assess intra-operative sagittal correction for TL-ASD. This summary chart takes into consideration the variations in LL and PT based on PI magnitude, respects the principles of restoration of appropriate lumbar shape and distribution of lordosis with L4–S1 lordosis being 35–40°, incorporates the proposed apex of lordosis put forth by Roussouly, and highlights the importance of the vertebral-pelvic angles individually and in relationship to one another (Table 1). Potential utility of this framework is highlighted by a case example of a 76-year-old female with concomitant regional and global malalignment in the sagittal and coronal planes from de-novo degenerative scoliosis (Figure 5). After undergoing a L3–S1 anterior lumbar interbody fusion and T10-pelvis posterior instrumented fusion with L1–S1 posterior column osteotomies, global coronal radiographic realignment targets (CSVL 0 cm; goal <2–3 cm), regional sagittal alignment parameters (LL 57°, goal ± 5° of PI; PT 19°; goal <20°; L4–S1 lordosis 43°; goal 35–40°) and global sagittal alignment parameters (C7–S1 SVA − 0.5 cm; goal <4 cm; L1PA − 7°; goal <7.5°; T4PA − 10°; goal <10–15°; T4–L1-hip axis − 3°; goal ± 4°) were all met. At 3 years post-operatively, she is without proximal junctional pathology and rod fractures and has no functional limitations.

Table 1

| Target | Low PI (<45 degree) | Middle PI (45–65 degree) | High PI (>65 degree) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coronal plane | |||

| CSVL | <2–3 cm | <2–3 cm | <2–3 cm |

| Sagittal plane | |||

| L1–S1 lordosis | PI + 10–15° | PI ± 5° | PI − 10–15° |

| L4–S1 lordosis | 35–40° (80–90% of PI) | 35–40° (~67% of PI) | 35–40° (50% of PI) |

| Apex of lordosis | L5 | L4–5 | L4 |

| PT | <10–15° | <20° | <25–30° |

| L1PA | (PI × 0.5) − 21° | (PI × 0.5) − 21° | (PI × 0.5) − 21° |

| T4PA | <10–15° | <10–15° | <10–15° |

| T4–L1-hip | ±4° | ±4° | ±4° |

PI, pelvic incidence; CSVL, central sacral vertical line; PT, pelvic tilt; PA, pelvic angle.

The strength of this manuscript is that it is a comprehensive review of both coronal and sagittal spinal alignment parameters and how they each influence patient outcomes following surgical correction of ASD. However, it has several limitations inherent to its focused topic. Specifically, this standard review article is without a discussion of how radiographic spinal alignment principles guide clinical and surgical decision making for both adults and children. Additionally, there is an absence of a complete review of the influence of radiographic spinal alignment parameters on PRO measures before surgical correction. Additionally, while the referenced articles in this review may not encompass all the literature on this topic given it is a standard review and not a formal narrative review, a meta-analysis, or a systemic review, the information in this review should be considered an accurate, unbiased, and most current portrayal of coronal and sagittal spinal alignment parameters and their respective influence on patient outcomes after surgical correction of ASD. Future review articles would benefit from addressing the aforementioned limitations.

Conclusions

Achievement of appropriate sagittal and coronal realignment in TL-ASD operations is critical for PROs and durability of the operations (prevention of long-term mechanical complications). While radiographic alignment targets continue to be refined, the following sentiments represent the most up-to-date consensus on radiographic spinal alignment parameters and patient outcomes. In the coronal plane, correcting the deformity to a CSVL <2–3 cm portends better patient outcomes. For the sagittal plane, adhering to PI-based alignment strategies (i.e., GAP score, T4–L1-hip axis), age-adjusted alignment guidelines, and recreating appropriate spinal shape based on Roussouly classification to achieve global body sagittal alignment (CrSVA) all likely play a role in the short- and long-term outcomes of patients. As such, pre-operative planning and intra-operative confirmation/evaluation of spinal alignment are necessary and critical for optimizing chances of attaining optimal clinical outcomes following adult thoracolumbar spinal deformity operations.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Mark J. Lambrechts and Munish C. Gupta) for the series “Adult Spinal Deformity: Principles, Approaches, and Advances” published in AME Surgical Journal. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://asj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/asj-24-34/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://asj.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/asj-24-34/coif). The series “Adult Spinal Deformity: Principles, Approaches, and Advances” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. A.A.T. reports being a consultant for Depuy Synthes Spine, Ulrich Medical USA, Surgalign Holdings, Restor3D, ICOtec, Carbofix Orthopedics, Smart Step Surgical, LLC, and Surgeon Design Center, LLC, receiving grant support from Alphatec Spine and Globus Medical, and being on Surgical Advisory Boards for Restor3D and Ulrich Medical USA. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Scheer JK, Smith JS, Clark AJ, et al. Comprehensive study of back and leg pain improvements after adult spinal deformity surgery: analysis of 421 patients with 2-year follow-up and of the impact of the surgery on treatment satisfaction. J Neurosurg Spine 2015;22:540-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Teles AR, Mattei TA, Righesso O, et al. Effectiveness of Operative and Nonoperative Care for Adult Spinal Deformity: Systematic Review of the Literature. Global Spine J 2017;7:170-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scheer JK, Hostin R, Robinson C, et al. Operative Management of Adult Spinal Deformity Results in Significant Increases in QALYs Gained Compared to Nonoperative Management: Analysis of 479 Patients With Minimum 2-Year Follow-Up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2018;43:339-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith JS, Lafage V, Shaffrey CI, et al. Outcomes of Operative and Nonoperative Treatment for Adult Spinal Deformity: A Prospective, Multicenter, Propensity-Matched Cohort Assessment With Minimum 2-Year Follow-up. Neurosurgery 2016;78:851-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Schwab F, Smith JS, et al. Likelihood of reaching minimal clinically important difference in adult spinal deformity: a comparison of operative and nonoperative treatment. Ochsner J 2014;14:67-77. [PubMed]

- Li G, Passias P, Kozanek M, et al. Adult scoliosis in patients over sixty-five years of age: outcomes of operative versus nonoperative treatment at a minimum two-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2165-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bridwell KH, Glassman S, Horton W, et al. Does treatment (nonoperative and operative) improve the two-year quality of life in patients with adult symptomatic lumbar scoliosis: a prospective multicenter evidence-based medicine study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:2171-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith JS, Shaffrey CI, Berven S, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of leg pain in adults with scoliosis: a retrospective review of a prospective multicenter database with two-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:1693-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Passias PG, Williamson TK, Mir JM, et al. Are We Focused on the Wrong Early Postoperative Quality Metrics? Optimal Realignment Outweighs Perioperative Risk in Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery. J Clin Med 2023;12:5565. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O’Brien MF, Kuklo TR, Blanke KM, Lenke LG. Spinal Deformity Study Group (SDSG) Radiographic Measurement Manual; 2004.

- Sharfman ZT, Clark AJ, Gupta MC, et al. Coronal Alignment in Adult Spine Surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2024;32:417-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glassman SD, Berven S, Bridwell K, et al. Correlation of radiographic parameters and clinical symptoms in adult scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:682-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buell TJ, Smith JS, Shaffrey CI, et al. Multicenter assessment of surgical outcomes in adult spinal deformity patients with severe global coronal malalignment: determination of target coronal realignment threshold. J Neurosurg Spine 2021;34:399-412. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boissiere L, Bourghli A, Kieser D, et al. Fixed coronal malalignment (CM) in the lumbar spine independently impacts disability in adult spinal deformity (ASD) patients when considering the obeid-CM (O-CM) classification. Spine J 2023;23:1900-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baroncini A, Frechon P, Bourghli A, et al. Adherence to the Obeid coronal malalignment classification and a residual malalignment below 20 mm can improve surgical outcomes in adult spine deformity surgery. Eur Spine J 2023;32:3673-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Acaroglu E, Guler UO, Olgun ZD, et al. Multiple Regression Analysis of Factors Affecting Health-Related Quality of Life in Adult Spinal Deformity. Spine Deform 2015;3:360-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim YC, Lenke LG, Lee SJ, et al. The cranial sagittal vertical axis (CrSVA) is a better radiographic measure to predict clinical outcomes in adult spinal deformity surgery than the C7 SVA: a monocentric study. Eur Spine J 2017;26:2167-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim YC, Cui JH, Kim KT, et al. Novel radiographic parameters for the assessment of total body sagittal alignment in adult spinal deformity patients. J Neurosurg Spine 2019;31:372-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai CS, Mohanty S, Hassan FM, et al. Cranial sagittal vertical axis to the hip as the best sagittal alignment predictor of patient-reported outcomes at 2 years postoperatively in adult spinal deformity surgery. J Neurosurg Spine 2024;41:774-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Protopsaltis T, Schwab F, Bronsard N, et al. TheT1 pelvic angle, a novel radiographic measure of global sagittal deformity, accounts for both spinal inclination and pelvic tilt and correlates with health-related quality of life. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:1631-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hills J, Lenke LG, Sardar ZM, et al. The T4-L1-Hip Axis: Defining a Normal Sagittal Spinal Alignment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2022;47:1399-406. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hills J, Mundis GM, Klineberg EO, et al. The T4-L1-Hip Axis: Sagittal Spinal Realignment Targets in Long-Construct Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery: Early Impact. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2024;106:e48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chanbour H, Waddell WH, Vickery J, et al. L1-pelvic angle: a convenient measurement to attain optimal deformity correction. Eur Spine J 2023;32:4003-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terran J, Schwab F, Shaffrey CI, et al. The SRS-Schwab adult spinal deformity classification: assessment and clinical correlations based on a prospective operative and nonoperative cohort. Neurosurgery 2013;73:559-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith JS, Klineberg E, Schwab F, et al. Change in classification grade by the SRS-Schwab Adult Spinal Deformity Classification predicts impact on health-related quality of life measures: prospective analysis of operative and nonoperative treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:1663-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lafage R, Schwab F, Challier V, et al. Defining Spino-Pelvic Alignment Thresholds: Should Operative Goals in Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery Account for Age? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:62-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vaz G, Roussouly P, Berthonnaud E, et al. Sagittal morphology and equilibrium of pelvis and spine. Eur Spine J 2002;11:80-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roussouly P, Gollogly S, Berthonnaud E, et al. Classification of the normal variation in the sagittal alignment of the human lumbar spine and pelvis in the standing position. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:346-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laouissat F, Sebaaly A, Gehrchen M, et al. Classification of normal sagittal spine alignment: refounding the Roussouly classification. Eur Spine J 2018;27:2002-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pizones J, Moreno-Manzanaro L, Sánchez Pérez-Grueso FJ, et al. Restoring the ideal Roussouly sagittal profile in adult scoliosis surgery decreases the risk of mechanical complications. Eur Spine J 2020;29:54-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sebaaly A, Gehrchen M, Silvestre C, et al. Mechanical complications in adult spinal deformity and the effect of restoring the spinal shapes according to the Roussouly classification: a multicentric study. Eur Spine J 2020;29:904-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bari TJ, Hansen LV, Gehrchen M. Surgical correction of Adult Spinal Deformity in accordance to the Roussouly classification: effect on postoperative mechanical complications. Spine Deform 2020;8:1027-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gessara A, Patel MS, Estefan M, et al. Restoration of the sagittal profile according to the Roussouly classification reduces mechanical complications and revision surgery in older patients undergoing surgery for adult spinal deformity (ASD). Eur Spine J 2024;33:563-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pesenti S, Lafage R, Stein D, et al. The Amount of Proximal Lumbar Lordosis Is Related to Pelvic Incidence. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2018;476:1603-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yilgor C, Sogunmez N, Boissiere L, et al. Global Alignment and Proportion (GAP) Score: Development and Validation of a New Method of Analyzing Spinopelvic Alignment to Predict Mechanical Complications After Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:1661-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho M, Lee S, Kim HJ. Assessing the predictive power of the GAP score on mechanical complications: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 2024;33:1311-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Passias PG, Krol O, Owusu-Sarpong S, et al. The Effects of Global Alignment and Proportionality Scores on Postoperative Outcomes After Adult Spinal Deformity Correction. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown) 2023;24:533-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ye J, Gupta S, Farooqi AS, et al. Predictive role of global spinopelvic alignment and upper instrumented vertebra level in symptomatic proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity. J Neurosurg Spine 2023;39:774-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wegner AM, Iyer S, Lenke LG, et al. Global alignment and proportion (GAP) scores in an asymptomatic, nonoperative cohort: a divergence of age-adjusted and pelvic incidence-based alignment targets. Eur Spine J 2020;29:2362-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kwan KYH, Lenke LG, Shaffrey CI, et al. Are Higher Global Alignment and Proportion Scores Associated With Increased Risks of Mechanical Complications After Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery? An External Validation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2021;479:312-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yagi M, Daimon K, Hosogane N, et al. Predictive Probability of the Global Alignment and Proportion Score for the Development of Mechanical Failure Following Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery in Asian Patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021;46:E80-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bari TJ, Ohrt-Nissen S, Hansen LV, et al. Ability of the Global Alignment and Proportion Score to Predict Mechanical Failure Following Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery-Validation in 149 Patients With Two-Year Follow-up. Spine Deform 2019;7:331-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quarto E, Zanirato A, Pellegrini M, et al. GAP score potential in predicting post-operative spinal mechanical complications: a systematic review of the literature. Eur Spine J 2022;31:3286-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Banno T, Hasegawa T, Yamato Y, et al. T1 Pelvic Angle Is a Useful Parameter for Postoperative Evaluation in Adult Spinal Deformity Patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:1641-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryan DJ, Protopsaltis TS, Ames CP, et al. T1 pelvic angle (TPA) effectively evaluates sagittal deformity and assesses radiographical surgical outcomes longitudinally. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2014;39:1203-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacobs E, van Royen BJ, van Kuijk SMJ, et al. Prediction of mechanical complications in adult spinal deformity surgery-the GAP score versus the Schwab classification. Spine J 2019;19:781-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Passias PG, Pierce KE, Raman T, et al. Does Matching Roussouly Spinal Shape and Improvement in SRS-Schwab Modifier Contribute to Improved Patient-reported Outcomes? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021;46:1258-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pizones J, Hills J, Kelly M, et al. Which sagittal plane assessment method is most predictive of complications after adult spinal deformity surgery? Spine Deform 2024;12:1127-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Das A, Onafowokan OO, Mir J, et al. The more the better? Integration of vertebral pelvic angles (VPA) PJK thresholds to existing alignment schemas for prevention of mechanical complications after adult spinal deformity surgery. Eur Spine J 2024;33:3887-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dial BL, Hills JM, Smith JS, et al. The impact of lumbar alignment targets on mechanical complications after adult lumbar scoliosis surgery. Eur Spine J 2022;31:1573-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenberg JK, Kelly MP, Landman JM, et al. Individual differences in postoperative recovery trajectories for adult symptomatic lumbar scoliosis. J Neurosurg Spine 2022;37:429-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chapman TM Jr, Baldus CR, Lurie JD, et al. Baseline Patient-Reported Outcomes Correlate Weakly With Radiographic Parameters: A Multicenter, Prospective NIH Adult Symptomatic Lumbar Scoliosis Study of 286 Patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:1701-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faraj SSA, De Kleuver M, Vila-Casademunt A, et al. Sagittal radiographic parameters demonstrate weak correlations with pretreatment patient-reported health-related quality of life measures in symptomatic de novo degenerative lumbar scoliosis: a European multicenter analysis. J Neurosurg Spine 2018;28:573-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Theologis AA. Adult thoracolumbar deformity: critical appraisal of radiographs, understanding the angles, and predictors of optimal patient improvement—a review. AME Surg J 2025;5:3.